Jason

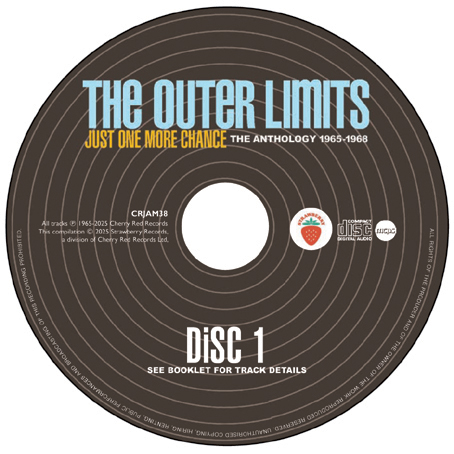

Barnard interviewed Jeff Christie for his podcast website,

Strange Brew, in July 2025, to coincide with the release

of the Outer Limits double-CD box set.

BEFORE Jeff Christie turned the global

dial to Yellow River, he was

at the helm of The

Outer Limits, a group that recorded some of the

most criminally overlooked British music of the 1960s. Now,

with an extensive new box set, Jeff reflects on the band

that was, the break that wasn't, and why, after all these

years, The Outer Limits weren't science fiction, they were

the real thing.

SB: What was it about Heartbreak

Hotel that struck such a deep chord?

JC: The sound

of the record soaked in echo, the haunting vocal and Scotty

Moore's guitar solo backed by Floyd Cramer's slowed down

boogie style piano. The song built its tension patiently

by only using a walking bass line punctuated by a double

strike chord against Elvis's tortured vocal, gradually filling

out with more tinkering high piano and subtle background

guitar licks till the end. Just over two minutes of glorious

excitement and new sounds after much of the anodyne 50's

pop music.

SB: Your parents had very different

musical tastes, opera and ballet versus crooners and swing.

How did those influences shape you?

JC: They all had the cumulative

effect of helping me appreciate all kinds of music. Certainly

this was bound to be reflected consciously or unconsciously

into my songwriting as nothing was out of bounds musically.

SB: Can you take us back to

the transition from the 3G's +1 and The Tremmers to becoming

The Outer Limits? How did the band names and sound evolve?

JC: The Tremmers emerged out

of the ashes of the 3G's +1 which was a short-lived group.

I think a couple of youth club performances and that was

it, but as the group folded I met several lads in that club

that could sing a bit or play some instrument.

I remember one day this older lad

brought his guitar into the cloakroom where I sometimes

would sit and play as it had great acoustics with loads

of room echo.

I knew how to play Walk

Don't Run by The Ventures and I was playing it as

he walked in. Some kids would come and go and some would

stop and listen for a bit but this lad sat down, asked me

what key it was in and joined in. He knew some chords and

so I told him the rest and we started to play.

We hit it off and decided to get

together in each other's houses to practise together. After

learning a few songs we would meet up in the youth club's

cloakroom and play a bit, when one day another older lad

came in with a biscuit tin and some drumming brushes and

joined in.

Now

there was three of us and what's more he had his own drum

kit. We knew another lad who played saxophone and he would

hang around and wanted to join us but we needed a bass player

as we now had two guitars, drums but no bass. He sold his

sax, got a bass guitar and would come over to my house and

I'd give him a few lessons till he got the hang of it and

now we were four: Gerry Layton, Stan Drogie, Rod Brooks

and me.

Now

there was three of us and what's more he had his own drum

kit. We knew another lad who played saxophone and he would

hang around and wanted to join us but we needed a bass player

as we now had two guitars, drums but no bass. He sold his

sax, got a bass guitar and would come over to my house and

I'd give him a few lessons till he got the hang of it and

now we were four: Gerry Layton, Stan Drogie, Rod Brooks

and me.

That was how The Tremmers started,

mainly an instrumental group playing Shadows, Ventures and

similar groups. We wanted a name that implied earthquakes

as that kind of name was in fashion. After a while we got

a couple of vocalists, one black for Little Richard numbers

and one white for doing the white rock'n'roll songs.

After a couple of years Rod left

to join another group and we carried on, first with a lad

called Ken until he left, and was replaced by Paul Cardus.

We then morphed into the Outer Limits when Paul left and

was replaced by Gerry Smith. We were all fans of a Sci-Fi

series called The Outer Limits and we thought that was a

great name for the group.

SB: At what point did you feel

ready to move from covers to your own compositions?

JC: When we (Outer Limits)

needed to get a recording contract, and it became obvious

the game was up doing covers. I think we failed maybe two

auditions, one for certain by playing covers. I remember

particularly one A&R man taking me to one side and saying

'you've got a good band but you need to write your own material

if you want to stand a chance of getting a contract'. That

was the defining moment and I then set about trying to write

songs so we would stand a better chance of being signed

to a record label.

SB: You crossed paths with

some incredible figures; from Reg Dwight in Bluesology to

Joe Cocker, Jimi Hendrix, and Bryan Ferry. Which of those

early encounters left the biggest impression?

JC: I have a distant memory

of running into Beach Boy Bruce Johnston outside some London

club one night in the seventies and was struck by how approachable,

he was, easy going and easy to talk to, unlike Harry Nilsson

who I met one winters night on a deserted Sunningdale station

while he was waiting for the train to Ascot to meet Lennon.

He was edgy and the total opposite of Bruce.

Undoubtedly of those you mentioned,

it would be Jimi Hendrix as he was unique. Reg had yet to

emerge as Elton when we (Outer Limits) were on the same

bill with him and just stayed in the background playing

keyboards with Bluesology. Brian Ferry also was yet to emerge

as the lounge lizard of later fame, before which he sometimes

played records in the Jazz Lounge at the Club a Gogo Newcastle

when we used to play there in the Sixties. Joe Cocker was

still unknown, but being his backing group for a few numbers

in Sheffield, one time confirmed he was going to be a force

to be reckoned with: you could see he was also a bit unique

with that incredible voice and jerky stage presence. We

used to play at Pete Stringfellow's Mojo club occasionally

and one time Pete asked if a local lad could get up and

do a few numbers with us which he duly did, and was dynamite.

Jarvis was probably just learning to walk!

Being on tour with Jimi for three

weeks and having the opportunity to watch him perform day

in and day out was a privilege and a huge learning curve.

Everything about him, personality, guitar mastery, great

songs, showmanship, stage presence, he had it all! One can

argue about the guitar greats and who is the greatest but

if you want the whole package for my money he's the one,

major dude!

SB: That

story about Hank Marvin taking your advice on a chord

(for Kitty Lester's Love

Letters), did

that moment give you a new kind of confidence in your musicianship?

JC: Well firstly I suggested,

not advised, as that would have been a bit pompous of me

although you could say a bit cheeky, especially as he was

an idol of mine at that tender age. Even then, who knows

if he agreed or not. I feel almost sure he probably did

but I never heard a Shadows or Hank Marvin version of Love

Letters to confirm that chord one way or another.

I think the fact that the great one had spared us a few

minutes of his time to talk to us was a confidence booster

in itself, but I was also progressing rapidly and was known

at the time for being one of the best Hank Marvin copyists

in the Leeds area and the feedback from audiences were so

enthusiastic that that can't help but build confidence,

or arrogance, I hope it was the former.

SB: Many of the recordings

on this box set, like Sweet Freedom

and Someday Somehow, were demos

left unheard for decades. How does it feel to finally have

them out in the world?

JC: A little strange but also liberating. These demos

were never meant to be released in their form as they were

basically notepads intended for later polishing up before

better studio production would enable them for general release.

As is often the case when you write

lots of songs and styles and fashions change, some songs

just do not fit the mood of the era you are now in so they

get left behind until one day Cherry Red turn up and ask

me what rough diamonds are in the vault baby. At first I

was reluctant to let them hear these less than perfect demos

but they were quite persuasive and asked if they could at

least hear them so I sent them down London town and they

replied saying they were great and please could they include

them.

They said there was a substantial

market for these demos of that era as they were collector's

items with a dedicated fan base. So I acquiesced and if

for nothing else it is interesting to see the different

styles, progression and experimentation in songwriting from

those first arguably charming beginnings to hopefully a

more mature higher standard later on.

SB: Your songs from that time

often feel filled with quiet longing; not just for love,

but for change, for escape, for something just out of reach.

Where do you think that sense of yearning came from?

JC: All those things but isn't

it a universal longing to love, be loved, understood and

the constant striving for some kind of personal Nirvana

in the ever-changing landscape of an often unfriendly and

frightening world.

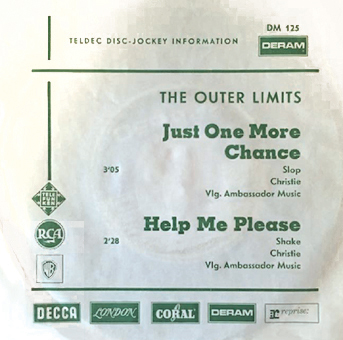

SB: The BBC's decision to not

play Great Train Robbery clearly

had an impact. Did censorship or industry politics often

get in the way of creative momentum?

JC: Well, it was definitely

a blow as it was the follow-up to Just

One More Chance, which had been a minor hit in the

UK and therefore arguably a stepping stone.

It made us lose the momentum of

following that early success by being banned for broadcast

by the only main radio station. The Shadows' original drummer

Tony Meehan, who scored the orchestration' told me years

later at a big BBC Millenium party it was deemed too political

as it hinted at the infamous GTR of the sixties even if

the song said it was in 1899, although in the original demo

version I sang 1949, close but no cigar!

I did learn a lesson as it inspired

a different approach to my writing which often became the

modus operendi in which the use of metaphor allows the writer

to mirror autobiographic experiences onto other subject

matter at times, or write an ambiguous lyric that means

different things to different people, which may or may not

be what the writer is thinking about at source.

Sometimes though it is an obvious

choice to write a direct lyric with no hidden meanings.

Ultimately it comes down to what mood I am in when I'm in

writing mode.

SB: You've

described your time in The Outer Limits as an apprenticeship.

Was there a moment on the 1967 tour with Pink Floyd, The

Move, and Amen Corner that encapsulates that era for you?

JC: Yes, it was in some ways

a second-tier apprenticeship as I'd already served my first

having six or seven-years' experience under my belt and

in my third group. But this tour experience was invaluable

watching Jimi every night but also The Move and The Nice

were great to watch and how they used the stage. Floyd and

Amen Corner weren't movers or exciting for me, but Keith

Emerson throwing daggers into his Hammond and at Hendrix,

who egged him on from the wings, were.

The standout memory from that tour

was watching Jimi from the wings and the audience response,

and on one occasion at Newcastle City Hall he was having

problems with the tuning of his Gibson Flying V and getting

increasingly frustrated trying to keep it in tune. He would

sometimes close his set with the Troggs Wild Thing as he

did on this occasion and would work the top line melody

of 'Strangers in the Night'

into his guitar solo which was a little bizarre but at the

same time brilliant even though totally off the wall. It

got so bad that he finally lost patience, turned and threw

his arrow shaped guitar at his Marshall Stack from roughly

a seven-yard distance.

Instead of either missing or falling

short it hit bull's eye centre speaker, quivering with feedback

way north of 11 whilst emitting some sort of grey black

smoke from the stricken amp as it rocked back and forth

under the assault, Lemmy his roadie at the time most probably

standing behind it to stop it toppling over.

Mitch Mitchell, not to be outdone,

kicked over his drum kit, Keith Moon style, leaving Noel

Redding, sole survivor, grimly trying to carry on playing

bass. The whole stage now a demolition zone.

I was standing in the wings watching

next to Carl Wayne of The Move and we just looked at each

other in awe as did much of the audience who went ballistic!

A part of me was horrified at that beautiful Stratocaster

breaking and burnt demise, not to mention collateral damage

to drums, mics and amps etc, particularly as we less successful

groups were so short of funds to buy or maintain equipment,

but at the same time recognising this as shock and awe rock

and roll theatre although it was already not new as Townshend

and Moon had already paved the way.

.jpg)

SB: The Outer Limits had a

strong Yorkshire following. What ultimately led to the band

calling it a day despite those signs of promise?

JC: We were demoralised and

broke after getting so close to breaking through and especially

after the highs of being on that tour. I tried to keep everyone

together for one more push but as can be seen in the Yorkshire

TV documentary 'Death

Of A Pop Group', the lads were not for turning

so I just had to carry on believing, and resigned to carry

on alone and without a band.

I set my sights on breaking through

as a songwriter and maybe if success came, a new outfit

would follow: as was the case a couple of years later but

that's another story.

SB: With so many line-up changes

and near-breakthroughs, did you ever feel the music industry

was more about luck than talent?

JC: Sometimes it felt that

way though I think you need both, but you have to make your

own luck by being focused, determined and relentless and

not get disheartened every time you hit a brick wall. At

the same time be as good as you can be at whatever it is

you want to be successful at. In my case I tried to be all

that. I loved making music and was very determined and hungry

and from day one in my early teens knew this was my life

choice as there was nothing else that motivated me, apart

from maybe girls.

SB: Just

One More Chance and Sweet Freedom

are standout examples of your early writing. How would you

describe your songwriting process back then compared to

now?

JC: I always try to write a

strong melody and try and combine that with an appropriate

lyric. That was and has always been the driver. I want to

write memorable songs that firstly please me and then hopefully

please others.

I hope in some ways I've improved

and matured sonically and lyrically over the years but never

lost that sense of simplicity that should underpin my efforts

even though I tend to use more complex chord sequences than

in my earliest attempts.

SB: Listening to this box set,

it's clear that The Outer Limits' music stands on its own,

inventive, melodic, and emotionally rich. Do you feel the

group is finally getting the recognition it deserves?

JC: Thank you for that generous

assessment. In some ways the fact that Cherry Red have recogniSed

its potential and are now vigorously promoting this Outer

Limits Anthology release speaks volumes.